- Home

- Patricia Highsmith

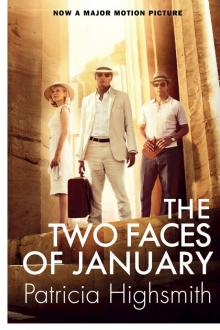

The Two Faces of January

The Two Faces of January Read online

The

Two Faces

of January

BOOKS BY

PATRICIA HIGHSMITH

NOVELS

Strangers on a Train

The Blunderer

The Talented Mr. Ripley

Deep Water

A Game for the Living

The Cry of the Owl

This Sweet Sickness

The Two Faces of January

The Glass Cell

A Suspension of Mercy

Those Who Walk Away

The Tremor of Forgery

Ripley Under Ground

A Dog’s Ransom

Ripley’s Game

Edith’s Diary

The Boy Who Followed Ripley

People Who Knock on the Door

Found in the Street

Ripley Under Water

SHORT STORIES

Eleven

The Animal-Lover’s Book of Beastly Murder

Little Tales of Misogyny

Slowly, Slowly in the Wind

The Black House

Mermaids on the Golf Course

Tales of Natural and Unnatural Catastrophes

The

Two Faces

of January

Patricia Highsmith

Grove Press

New York

Copyright © 1964 by Patricia Highsmith

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or [email protected].

The poem on pages 186–187 is reprinted by permission of Robert Mitchell from the book The End, Pineapple Press, 1961.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The two faces of January.

Reprint.

I. Title.

PS3558.I366T8 1988 813'.54—dc20 87-30669

ISBN 978-0-8021-2262-9

eISBN 978-0-8021-9242-4

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

For my friend

Rolf Tietgens

I

At half past three of a morning in early January, Chester MacFarland was awakened in his berth on the San Gimignano by an alarming sound of scraping. He sat up and saw through the porthole a brightly lighted wall of orangey-red color, extremely close and creeping by. His first thought was that they were grazing the side of another ship, and he scrambled out of bed and, still half asleep, leaned across his wife’s berth and looked more closely. There were scribblings and scratches and numbers on the wall, which he now saw was rock. NIKO 1957, he read. W. MUSSOLINI. Then an American-looking PETE ’6o.

The alarm clock went off, and Chester grabbed for it, knocking over the Scotch bottle that stood beside it on the floor. He pressed the button that stopped the alarm, then reached for his robe.

“Darling?—What’s going on?” Colette asked sleepily.

“I think we’re in the Corinthian Canal,” Chester said. “Or else we’re awfully close to another ship. We’re due to be in the canal. It’s half past three. Coming on deck?”

“Um-m—no,” Colette murmured, snuggling deeper into the bedclothes. “You tell me all about it.”

Smiling, Chester pressed a kiss into her warm cheek. “I’m going on deck. Back in a minute.”

As soon as he stepped out of the door onto the deck, Chester ran into the officer who had told him they would pass through the canal at 3:30 a.m.

“Sississi! Il canale, signor!” he said to Chester.

“Thanks!” Chester felt a thrill of adventure and excitement, and stood erect against the chill wind, gripping the rail with both hands. There was no one but him on the deck.

The canal’s sides looked four storys high, at least. Leaning over the rail, Chester saw only blackness at either end of the canal. It was impossible to see just how long it was, but he remembered its length on his map of Greece, one half inch, which he thought would be about four miles. Man-made, this vital waterway. The thought gave him pleasure. Chester looked at the marks of drills and pickaxes that were still visible in the orangey rock—or was it hard clay? Chester lifted his eyes to where the side of the canal stopped sharp against the darkness, looked higher to the stars sprinkled in the Grecian sky. In just a few hours, he would see Athens. He had an impulse to stay up the rest of the night, to get his overcoat and stand on deck while the ship ploughed through the Aegean towards Piraeus. He’d be tired tomorrow, however. After a few minutes, Chester went back to the stateroom and crawled into bed.

Some five hours later, when the San Gimignano had docked at Piraeus, Chester was pushing his way towards the rail through a grumbling tangle of passengers and porters who had come aboard to assist people with their luggage. Chester had breakfasted in a leisurely way in his state-room, preferring to wait until the majority of the passengers had debarked; but, judging from the number of people on deck and in the corridors, the debarking had not even begun. The town and the dock of Piraeus looked like a dusty mess. Chester was disappointed not to be able to see Athens in the hazy distance. He lit a cigarette and looked slowly over the moving and stationary figures on the broad expanse of dock. Blue-clad porters. A few men in rather shabby-looking overcoats walking about restlessly, glancing at the ship: they looked more like money-changers or taxi-drivers than policemen, Chester thought. His eyes moved from left to right and back again over the entire scene. No, he couldn’t believe that any one of the men he saw could be waiting for him. The gangplank was down, and if anyone had come for him, wouldn’t he be coming right on board now, instead of waiting on the dock? Of course. Chester cleared his throat and took a gentle drag on his cigarette. Then he turned and saw Colette.

“Greece,” she said, smiling.

“Yes. Greece.” He took her hand. Her fingers spread, then closed tightly on his. “I’d better see about a porter. All the suitcases closed?”

She nodded. “I saw Alfonso. He’ll bring them out.”

“Did you tip him?”

“Um-m. Two thousand lire. You think that’s okay?” Her dark-blue eyes looked up widely at Chester. Her long auburn lashes blinked twice. Then she repressed a laugh that came bubbling out of her, a laugh of happiness and affection. “You’re not thinking. Is two thousand enough?”

“Two thousand is perfect, darling.” Chester kissed her lips quickly.

Alfonso emerged with half their luggage, set it on the deck and went back for the rest. Chester helped him carry it down the gangplank to the dock, and then three or four porters began arguing as to who would get to carry it.

“Wait! Just wait, please,” Chester said. “Money, you know. Got to change some.” He waved his traveler’s check book, then trotted off to a money-changing booth near the gates of the dock. He changed a twenty.

“Please,” Colette said, patting a suitcase protectively, and the quarrelling porters folded their arms, stepped back and waited, looking her over with approval.

Colette—it was a name she had chosen for herself at the age of fourteen, in preference to Elizabeth—was twenty-five years old, five feet three, with reddish light-brown hair, full lips, a perfectly straight nose lightly sprinkled with freckles, and quite arrestingly pretty dark-blue, almost lavender, eyes. Her eyes looked widely and straightforwardly at everything and everyone, like the eyes of a curious, intelligent and still learning child. Men whom she looked at usually felt transfixed and fascinated by her gaze; there was something speculative in it, and nearly every man, whatever his age, thought, “She looks as if she’s falling in love with me. Could it be?” Most women thought her expression and even Colette herself rather naïve, too naïve to be dangerous; which was fortunate, because otherwise women might have been jealous or suspicious of her attractiveness. She had been married to Chester just a little more than a year, and she had met him by answering an advertisement he put in the Times for a part-time secretary and typist. It hadn’t taken her more than two days to realize that Chester’s business was not exactly on the up and up—what stockbroker operated out of his apartment instead of an office, and where were his stocks on the Exchange, anyway?—but Chester had a lot of charm; he plainly had plenty of money, and evidently the money was rolling in steadily, which meant he wasn’t in any trouble. Chester had been married before, for eight years, to a woman who had died of cancer two years before Colette met him. Chester was forty-two, still handsome, graying slightly at the temples, and just a bit inclined to develop a tummy, but Colette was inclined to put weight on all over, and dieting was a normal thing with her. It was easy for her to plan menus that were appetizing as well as low in calories.

“Here we go,” Chester said, waving a fistful of drachma notes. “Pick a taxi, honey.”

There were half a dozen taxis standing about, and Colette chose the one of a driver who had a friendly smile. Three porters helped them load the taxi with their seven pieces of luggage, two of which went on the roof, and then they were off for Athens. Chester sat forward, watching for the Parthenon on its hill, or some other landmark that might appear against the pale-blue sky. And then he found himself looking at an imaginary Walkie Kar, big as all Athens, red and chromium, with its horrible rubber-lumped handlebars and its ugly, cupped safety seat. Chester shuddered. What a stupidity, what a needless, idiotic risk that had been! Colette had told him so, too. She had got a bit angry when she found out about it, and she was perfectly justified in getting angry. The Walkie Kar had come about like this: in a printer’s shop where he was having some business cards made up, Chester had noticed a stack of handbills advertising the Walkie Kar. There was a picture of it, a description, and the price, $12.95, and at the bottom an order blank that could be torn off along a perforated line. The printer had laughed when Chester picked up one of the sheets and looked at it. The company was out of business, the printer said, and they hadn’t even paid him for his print job. No, the printer wouldn’t mind at all if Chester took a few of them, because he was going to throw them all out, anyway. Chester had said he wanted to send them to a few of his friends as a joke, his heavy-drinking friends, and at first he had wanted to do that only; and then something—temptation, bravado, a sense of humor?—had compelled him to try peddling the damned things, and by ringing doorbells and making with the old spiel he had sold more than eight-hundred dollars’ worth, mainly to people in the Bronx. Then he had run into one of his purchasers in his own apartment building in Manhattan, and, moreover, just as he was opening his own mailbox. The man said his Walkie Kar had not arrived, though he had ordered and paid for it two months ago, and neither had the Walkie Kar of a neighbor of his arrived. When that happened to two people who knew each other, they got together and did something about it, Chester knew from experience; and, since the man had taken a good look at his name on the mailbox, Chester had thought it just as well to get out of the country for a while, rather than move to another apartment and change his name to something else again. Colette had been wanting to go to Europe and they had planned to go in spring, but the Walkie Kar incident had hurried them up by four months. They had left New York in December. Yes, Colette had reproached him pretty severely for the Walkie Kar episode, and she had been annoyed also because she thought the weather wouldn’t be as pleasant in winter as in spring, and she was right, of course. Chester had given her a new set of luggage and a mink jacket by way of making it up to her, and he wanted to do everything he could to make the trip a happy one for her. It was Colette’s first trip to Europe. So far she had liked London best, and, to Chester’s surprise, liked London more than Paris. It had rained more in Paris than in London; Chester had caught a cold; and he remembered that every time he got his feet wet or felt rain sliding down the back of his neck, he had thought of the God-damned Walkie Kar, and he had reminded himself that for the wretched bit of money he had got out of it, he might have caused, might still cause, Howard Cheever (which was his current alias and the name that had been on his mailbox in the New York apartment building) to be exposed to a thorough investigation, which could mean the end of half a dozen companies on whose stock sales Chester depended for his living. Europe was safer than the States just now, and Chester MacFarland, his real name, was a name he hadn’t used in fifteen years; but he was guilty, among other things, of defrauding through the mails, which was one of the few offenses the American Government could extradite a man for. It was remotely possible that they would send a man over after him, Chester thought, if they ever made the connection between Cheever and MacFarland.

The taxi-driver asked him something over his shoulder in Greek.

“Sorry. No capeesh,” Chester answered. “The main square, okay? The centre of town.”

“Grande Bretagne?” asked the driver.

“Well . . . I’m not quite sure,” Chester said. The Grande Bretagne was unquestionably the biggest and best hotel in Athens, but for that very reason, Chester felt wary about stopping there. “Let’s take a look,” he added, though he didn’t think the driver understood. “There it is,” he said to Colette. “That white building over there.”

The white edifice of the Grande Bretagne had a formal, antiseptic air in contrast to the less tall and dirtier buildings and stores that stood around the rectangle of Constitution Square. There was a government building of some sort far to their right, a Greek flag flying from a pole on its grounds, and a couple of soldiers in skirts and white stockings standing guard near the doors.

“What about that hotel?” Chester asked, pointing. “The King’s Palace. That looks pretty good, don’t you think, honey?”

“Okay. Sure,” Colette said agreeably.

The King’s Palace Hotel was across a street at one side of the Grande Bretagne. A bellboy in a red jacket and black trousers came out on the pavement to help with the luggage. The lobby looked first-rate to Chester, maybe not luxury class, but first-rate. The carpet was thick underfoot, and, judging from the warmth, the central heating really worked.

“You have a reservation, sir?” asked the clerk behind the counter.

“No, no, we haven’t, but we’d like a room with a bath and a nice view,” Chester said, smiling.

“Yes, sir.” The clerk pushed a bell, then handed a key to the uniformed boy who came up. “Show them six twenty-one, please. May I have your passports, sir? You can pick them up when you come down.”

Chester took the one that Colette drew from her red leather case in her pocketbook, pulled his own from his inside breast pocket, and pushed them across the counter to the clerk. It always gave him a little throb of mental

pain, a small shock of embarrassment such as he felt when a doctor asked him to strip, whenever he pushed his passport over a hotel counter or had it taken from his hand by an official inspector. Chester Crighton MacFarland, five feet eleven, born in 1922 in Sacramento, California, no distinguishing marks, wife Elizabeth Talbott MacFarland. It was all so naked. Worst of all, his photograph, so untypically for a passport photograph, was a very good likeness, showing receding brown hair, aggressive jaw, good-sized nose, a rather stubborn, thin-lipped mouth with a moustache above it—an excellent portrait of him, depicting all but the color of his blue, staring eyes and the ruddiness of his cheeks. Had the clerk, Chester always thought, or the inspector been shown the same picture of him and told to keep his eyes open for him? This moment in the King’s Palace Hotel was not the time to learn, because the clerk pushed the passports to one side without opening them.

A few minutes later they were comfortably installed in a large, warm room with a view of the white, geranium garnished balconies of the Grande Bretagne and of a busy avenue six storys down, which Chester identified on his map of Athens as Venizelos Street. It was only 10 o’clock. The whole day lay before them.

2

At that moment, in a considerably cheaper and shabbier hotel around the corner on Kriezotou Street, sometimes called Jan Smuts Street, a young American named Rydal Keener was pressing the button for an elevator on the fourth floor. He was a slender, dark-haired young man, quiet and slow in movement. There was an air of melancholy about him, melancholy turned outward rather than inward, as if he brooded not on his own problems but the world’s. His dark eyes seemed to see and to think about whatever they looked at. He appeared also very poised, not at all concerned with what anybody thought of him. His insouciance was often taken for arrogance. It did not go with the worn shoes and overcoat he had on now, but his bearing was so confident that his clothes were the last thing people noticed about him, if they noticed them at all.

Small G: A Summer Idyll

Small G: A Summer Idyll The Boy Who Followed Ripley

The Boy Who Followed Ripley Edith's Diary

Edith's Diary Ripley's Game

Ripley's Game Mermaids on the Golf Course: Stories

Mermaids on the Golf Course: Stories Slowly, Slowly in the Wind

Slowly, Slowly in the Wind People Who Knock on the Door

People Who Knock on the Door The Glass Cell

The Glass Cell The Blunderer

The Blunderer Those Who Walk Away

Those Who Walk Away A Suspension of Mercy

A Suspension of Mercy Eleven

Eleven Found in the Street

Found in the Street Ripley Under Ground

Ripley Under Ground The Black House

The Black House The Cry of the Owl

The Cry of the Owl The Talented Mr. Ripley

The Talented Mr. Ripley This Sweet Sickness

This Sweet Sickness The Two Faces of January

The Two Faces of January The Animal-Lover's Book of Beastly Murder

The Animal-Lover's Book of Beastly Murder A Dog's Ransom

A Dog's Ransom Deep Water

Deep Water Strangers on a Train

Strangers on a Train Ripley Under Water

Ripley Under Water Small g

Small g Nothing That Meets the Eye

Nothing That Meets the Eye Patricia Highsmith - The Tremor of Forgery

Patricia Highsmith - The Tremor of Forgery Mermaids on the Golf Course

Mermaids on the Golf Course Suspension of Mercy

Suspension of Mercy The Price of Salt, or Carol

The Price of Salt, or Carol Glass Cell

Glass Cell