- Home

- Patricia Highsmith

The Price of Salt, or Carol Page 6

The Price of Salt, or Carol Read online

Page 6

“Terry, you know I’d rather be with you than anyone else in the world. That’s the hell of it.”

“Well, if it’s hell—”

“Do you love me at all, Terry? How do you love me?”

Let me count the ways, she thought. “I don’t love you, but I like you. I felt tonight, a few minutes ago,” she said, hammering the words out however they sounded, because they were true, “that I felt closer to you than I ever have, in fact.”

Richard looked at her, a little incredulously. “Do you?” He started slowly up the steps, smiling, and stopped just below her. “Then—why not let me stay with you tonight, Terry? Just let’s try, will you?”

She had known from his first step toward her that he was going to ask her that. Now she felt miserable and ashamed, sorry for herself and for him, because it was so impossible, and so embarrassing because she didn’t want it. There was always that tremendous block of not even wanting to try it, which reduced it all to a kind of wretched embarrassment and nothing more, each time he asked her. She remembered the first night she had let him stay, and she writhed again inwardly. It had been anything but pleasant, and she had asked right in the middle of it, “Is this right?” How could it be right and so unpleasant, she had thought. And Richard had laughed, long and loud and with a heartiness that had made her angry. And the second time had been even worse, probably because Richard had thought all the difficulties had been gotten over. It was painful enough to make her weep, and Richard had been very apologetic and had said she made him feel like a brute. And then she had protested that he wasn’t. She knew very well that he wasn’t, that he was angelic compared to what Angelo Rossi would have been, for instance, if she had slept with him the night he stood here on the same steps, asking her the same question.

“Terry, darling—”

“No,” Therese said, finding her voice at last. “I just can’t tonight, and I can’t go to Europe with you either,” she finished with an abject and hopeless frankness.

Richard’s lips parted in a stunned way. Therese could not bear to look at the frown above them. “Why not?”

“Because. Because I can’t,” she said, every word agony. “Because I don’t want to sleep with you.”

“Oh, Terry!” Richard laughed. “I’m sorry I asked you. Forget about it, honey, will you? And in Europe, too?”

Therese looked away, noticed Orion again, tipped at a slightly different angle, and looked back at Richard. But I can’t, she thought. I’ve got to think about it sometime, because you think about it. It seemed to her that she spoke the words and that they were solid as blocks of wood in the air between them, even though she heard nothing. She had said the words before to him, in her room upstairs, once in Prospect Park when she was winding a kite string. But he wouldn’t consider them, and what could she do now, repeat them? “Do you want to come up for a while anyway?” she asked, tortured by herself, by a shame she could not really account for.

“No,” Richard said with a soft laugh that shamed her all the more for its tolerance and its understanding. “No, I’ll go on. Good night, honey. I love you, Terry.” And with a last look at her, he went.

6

Therese stepped out into the street and looked, but the streets were empty with a Sunday morning emptiness. The wind flung itself around the tall cement corner of Frankenberg’s as if it were furious at finding no human figure there to oppose. No one but her, Therese thought, and grinned suddenly at herself. She might have thought of a more pleasant place to meet than this. The wind was like ice against her teeth. Carol was a quarter of an hour late. If she didn’t come, she would probably keep on waiting, all day and into the night. One figure came out of the subway’s pit, a splintery thin hurrying figure of a woman in a long black coat under which her feet moved as fast as if four feet were rotating on a wheel.

Then Therese turned around and saw Carol in a car drawn up by the curb across the street. Therese walked toward her.

“Hi!” Carol called, and leaned over to open the door for her.

“Hello. I thought you weren’t coming.”

“Awfully sorry I’m late. Are you freezing?”

“No.” Therese got in and pulled the door shut. The car was warm inside, a long dark green car with dark green leather upholstery. Carol drove slowly west.

“Shall we go out to the house? Where would you like to go?”

“It doesn’t matter,” Therese said. She could see freckles along the bridge of Carol’s nose. Her short fair hair that made Therese think of perfume held to a light was tied back with the green and gold scarf that circled her head like a band.

“Let’s go out to the house. It’s pretty out there.”

They drove uptown. It was like riding inside a rolling mountain that could sweep anything before it, yet was absolutely obedient to Carol.

“Do you like driving?” Carol asked without looking at her. She had a cigarette in her mouth. She drove with her hands resting lightly on the wheel, as if it were nothing to her, as if she sat relaxed in a chair somewhere, smoking. “Why’re you so quiet?”

They roared into the Lincoln Tunnel. A wild, inexplicable excitement mounted in Therese as she stared through the windshield. She wished the tunnel might cave in and kill them both, that their bodies might be dragged out together. She felt Carol glancing at her from time to time.

“Have you had breakfast?”

“No, I haven’t,” Therese answered. She supposed she was pale. She had started to have breakfast, but she had dropped the milk bottle in the sink, and then given it all up.

“Better have some coffee. It’s there in the thermos.”

They were out of the tunnel. Carol stopped by the side of the road.

“There,” Carol said, nodding at the thermos between them on the seat. Then Carol took the thermos herself and poured some into the cup, steaming and light brown.

Therese looked at the coffee gratefully. “Where’d it come from?”

Carol smiled. “Do you always want to know where things come from?”

The coffee was very strong and a little sweet. It sent strength through her. When the cup was half empty, Carol started the car. Therese was silent. What was there to talk about? The gold four-leaf clover with Carol’s name and address on it that dangled from the key chain on the dashboard? The stand of Christmas trees they passed on the road? The bird that flew by itself across a swampy-looking field? No. Only the things she had written to Carol in the unmailed letter were to be talked about, and that was impossible.

“Do you like the country?” Carol asked as they turned into a smaller road.

They had just driven into a little town and out of it. Now on the driveway that made a great semicircular curve, they approached a white two-story house that had projecting side wings like the paws of a resting lion.

There was a metal doormat, a big shining brass mailbox, a dog barking hollowly from around the side of the house, where a white garage showed beyond some trees. The house smelled of some spice, Therese thought, mingled with a separate sweetness that was not Carol’s perfume either. Behind her, the door closed with a light, firm double report. Therese turned and found Carol looking at her puzzledly, her lips parted a little as if in surprise, and Therese felt that in the next second Carol would ask, “What are you doing here?” as if she had forgotten, or had not meant to bring her here at all.

“There’s no one here but the maid. And she’s far away,” Carol said, as if in reply to some question of Therese’s.

“It’s a lovely house,” Therese said, and saw Carol’s little smile that was tinged with impatience.

“Take off your coat.” Carol took the scarf from around her head and ran her fingers through her hair. “Wouldn’t you like a little breakfast? It’s almost noon.”

“No, thanks.”

Carol looked around

the living room, and the same puzzled dissatisfaction came back to her face. “Let’s go upstairs. It’s more comfortable.”

Therese followed Carol up the wide wooden staircase, past an oil painting of a small girl with yellow hair and a square chin like Carol’s, past a window where a garden with an S-shaped path, a fountain with a blue-green statue appeared for an instant and vanished. Upstairs, there was a short hall with four or five rooms around it. Carol went into a room with green carpet and walls, and took a cigarette from a box on a table. She glanced at Therese as she lighted it. Therese didn’t know what to do or say, and she felt Carol expected her to do or say something, anything. Therese studied the simple room with its dark green carpet and the long green pillowed bench along one wall. There was a plain table of pale wood in the center. A game room, Therese thought, though it looked more like a study with its books and music albums and its lack of pictures.

“My favorite room,” Carol said, walking out of it. “But that’s my room over there.”

Therese looked into the room opposite. It had flowered cotton upholstery and plain blonde woodwork like the table in the other room. There was a long plain mirror over the dressing table, and throughout a look of sunlight, though no sunlight was in the room. The bed was a double bed. And there were military brushes on the dark bureau across the room. Therese glanced in vain for a picture of him. There was a picture of Carol on the dressing table, holding up a small girl with blonde hair. And a picture of a woman with dark curly hair, smiling broadly, in a silver frame.

“You have a little girl, haven’t you?” Therese asked.

Carol opened a wall panel in the hall. “Yes,” she said. “Would you like a Coke?”

The hum of the refrigerator came louder now. Through all the house, there was no sound but those they made. Therese did not want the cold drink, but she took the bottle and carried it downstairs after Carol, through the kitchen and into the back garden she had seen from the window. Beyond the fountain were a lot of plants some three feet high and wrapped in burlap bags that looked like something, standing there in a group, Therese thought, but she didn’t know what. Carol tightened a string that the wind had loosened. Stooped in the heavy wool skirt and the blue cardigan sweater, her figure looked solid and strong, like her face, but not like her slender ankles. Carol seemed oblivious of her for several minutes, walking about slowly, planting her moccasined feet firmly, as if in the cold flowerless garden she was at last comfortable. It was bitterly cold without a coat, but because Carol seemed oblivious of that, too, Therese tried to imitate her.

“What would you like to do?” Carol asked. “Take a walk? Play some records?”

“I’m very content,” Therese told her.

She was preoccupied with something, and regretted after all inviting her out to the house, Therese felt. They walked back to the door at the end of the garden path.

“And how do you like your job?” Carol asked in the kitchen, still with her air of remoteness. She was looking into the big refrigerator. She lifted out two plates covered with wax paper. “I wouldn’t mind some lunch, would you?”

Therese had intended to tell her about the job at the Black Cat Theater. That would count for something, she thought, that would be the single important thing she could tell about herself. But this was not the time. Now she replied slowly, trying to sound as detached as Carol, though she heard her shyness predominating, “I suppose it’s educational. I learn how to be a thief, a liar, and a poet all at once.” Therese leaned back in the straight chair so her head would be in the warm square of sunlight. She wanted to say, and how to love. She had never loved anyone before Carol, not even Sister Alicia.

Carol looked at her. “How do you become a poet?”

“By feeling things—too much, I suppose,” Therese answered conscientiously.

“And how do you become a thief?” Carol licked something off her thumb and frowned. “You don’t want any caramel pudding, do you?”

“No, thank you. I haven’t stolen yet, but I’m sure it’s easy there. There are pocketbooks all around, and one just takes something. They steal the meat you buy for dinner.” Therese laughed. One could laugh at it with Carol. One could laugh at anything, with Carol.

They had sliced cold chicken, cranberry sauce, green olives, and crisp white celery. But Carol left her lunch and went into the living room. She came back carrying a glass with some whiskey in it, and added some water to it from the tap. Therese watched her. Then for a long moment, they looked at each other, Carol standing in the doorway and Therese at the table, looking over her shoulder, not eating.

Carol asked quietly, “Do you meet a lot of people across the counter this way? Don’t you have to be careful whom you start talking to?”

“Oh, yes,” Therese smiled.

“Or whom you go out to lunch with?” Carol’s eyes sparkled. “You might run into a kidnapper.” She rolled the drink around in the iceless glass, then drank it off, the thin silver bracelets on her wrist rattling against the glass. “Well—do you meet many people this way?”

“No,” Therese said.

“Not many? Just three or four?”

“Like you?” Therese met her eyes steadily.

And Carol looked fixedly at her, as if she demanded another word, another phrase from Therese. But then she set the glass down on the stove top and turned away. “Do you play the piano?”

“Some.”

“Come and play something.” And when Therese started to refuse, she said imperatively, “Oh, I don’t care how you play. Just play something.”

Therese played some Scarlatti she had learned at the Home. In a chair on the other side of the room, Carol sat listening, relaxed and motionless, not even sipping the new glass of whiskey and water. Therese played the C major Sonata, which was slowish and rather simple, full of broken octaves, but it struck her as dull, then pretentious in the trill parts, and she stopped. It was suddenly too much, her hands on the keyboard that she knew Carol played, Carol watching her with her eyes half closed, Carol’s whole house around her, and the music that made her abandon her-self, made her defenseless. With a gasp, she dropped her hands in her lap.

“Are you tired?” Carol asked calmly.

The question seemed not of now but of always. “Yes.”

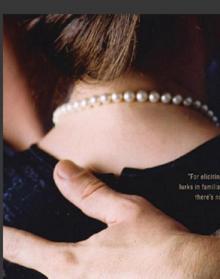

Carol came up behind her and set her hands on Therese’s shoulders. Therese could see her hands in her memory—flexible and strong, the delicate tendons showing as they pressed her shoulders. It seemed an age as her hands moved toward her neck and under her chin, an age of tumult so intense it blotted out the pleasure of Carol’s tipping her head back and kissing her lightly at the edge of her hair. Therese did not feel the kiss at all.

“Come with me,” Carol said.

She went with Carol upstairs again. Therese pulled herself up by the banister and was reminded suddenly of Mrs. Robichek.

“I think a nap wouldn’t hurt you,” Carol said, turning down the flowered cotton bedspread and the top blanket.

“Thanks, I’m not really—”

“Slip your shoes off,” Carol said softly, but in a tone that commanded obedience.

Therese looked at the bed. She had hardly slept the night before. “I don’t think I shall sleep, but if I do—”

“I’ll wake you in half an hour.” Carol pulled the blanket over her when she lay down. Carol sat down on the edge of the bed. “How old are you, Therese?”

Therese looked up at her, unable to bear her eyes now but bearing them nevertheless, not caring if she died that instant, if Carol strangled her, prostrate and vulnerable in her bed, the intruder. “Nineteen.” How old it sounded. Older than ninety-one.

Carol’s eyebrows frowned, though she smiled a little. Therese felt that she thought of something so intensely, one might have touched the thought in the air between them. Then Carol slipped her hands under her s

houlders, and bent her head down to Therese’s throat, and Therese felt the tension go out of Carol’s body with the sigh that made her neck warm, that carried the perfume that was in Carol’s hair.

“You’re a child,” Carol said, like a reproach. She lifted her head. “What would you like?”

Therese remembered what she had thought of in the restaurant, and she set her teeth in shame.

“What would you like?” Carol repeated.

“Nothing, thanks.”

Carol got up and went to her dressing table and lighted a cigarette. Therese watched her through half-closed lids, worried by Carol’s restlessness, though she loved the cigarette, loved to see her smoke.

“What would you like, a drink?”

Therese knew she meant water. She knew from the tenderness and the concern in her voice, as if she were a child sick with fever. Then Therese said it: “I think I’d like some hot milk.”

The corner of Carol’s mouth lifted in a smile. “Some hot milk,” she mocked. Then she left the room.

And Therese lay in a limbo of anxiety and sleepiness all the long while until Carol reappeared with the milk in a straight-sided white cup with a saucer under it, holding the saucer and the cup handle, and closing the door with her foot.

“I let it boil and it’s got a scum on it,” Carol said, sounding annoyed. “I’m sorry.”

But Therese loved it, because she knew this was exactly what Carol would always do, be thinking of something else and let the milk boil.

“Is that the way you like it? Plain like that?”

Therese nodded.

“Ugh,” Carol said, and sat down on the arm of a chair and watched her.

Therese was propped on one elbow. The milk was so hot, she could barely let her lip touch it at first. The tiny sips spread inside her mouth and released a mélange of organic flavors. The milk seemed to taste of bone and blood, of warm flesh, or hair, saltless as chalk yet alive as a growing embryo. It was hot through and through to the bottom of the cup, and Therese drank it down, as people in fairy tales drink the potion that will transform, or the unsuspecting warrior the cup that will kill. Then Carol came and took the cup, and Therese was drowsily aware that Carol asked her three questions, one that had to do with happiness, one about the store, and one about the future. Therese heard herself answering. She heard her voice rise suddenly in a babble, like a spring that she had no control over, and she realized she was in tears. She was telling Carol all that she feared and disliked, of her loneliness, of Richard, and of gigantic disappointments. And of her parents. Her mother was not dead. But Therese had not seen her since she was fourteen.

Small G: A Summer Idyll

Small G: A Summer Idyll The Boy Who Followed Ripley

The Boy Who Followed Ripley Edith's Diary

Edith's Diary Ripley's Game

Ripley's Game Mermaids on the Golf Course: Stories

Mermaids on the Golf Course: Stories Slowly, Slowly in the Wind

Slowly, Slowly in the Wind People Who Knock on the Door

People Who Knock on the Door The Glass Cell

The Glass Cell The Blunderer

The Blunderer Those Who Walk Away

Those Who Walk Away A Suspension of Mercy

A Suspension of Mercy Eleven

Eleven Found in the Street

Found in the Street Ripley Under Ground

Ripley Under Ground The Black House

The Black House The Cry of the Owl

The Cry of the Owl The Talented Mr. Ripley

The Talented Mr. Ripley This Sweet Sickness

This Sweet Sickness The Two Faces of January

The Two Faces of January The Animal-Lover's Book of Beastly Murder

The Animal-Lover's Book of Beastly Murder A Dog's Ransom

A Dog's Ransom Deep Water

Deep Water Strangers on a Train

Strangers on a Train Ripley Under Water

Ripley Under Water Small g

Small g Nothing That Meets the Eye

Nothing That Meets the Eye Patricia Highsmith - The Tremor of Forgery

Patricia Highsmith - The Tremor of Forgery Mermaids on the Golf Course

Mermaids on the Golf Course Suspension of Mercy

Suspension of Mercy The Price of Salt, or Carol

The Price of Salt, or Carol Glass Cell

Glass Cell